Author : Jonathan Glancey

António da Madelena, a Portuguese Capuchin friar, was one of the first Western visitors to Angkor Wat, the monumental and moated 12th Century Hindu-Buddhist temple in what, today, is northern Cambodia. It “is of such extraordinary construction”, he told the historian Diogo do Couto in 1589, “that it is not possible to describe it with a pen, particularly since it is like no other building in the world. It has towers and decoration and all the refinements which the human genius can conceive of.”

By the time of Madelena’s visit, the once mighty Khmer Empire that had built Angkor and its temple dedicated to Vishnu – mistaken by visitors even today for a walled and towered city – had fallen. Three centuries later, Europeans were baffled by what they found at Angkor. Henri Mouhout, a young French naturalist and explorer who died here in 1861 and whose writings, published posthumously, encouraged successive waves of archaeologists to Cambodia in pursuit of a lost ancient civilisation, could make neither head nor tail of what he saw.

“One of these temples – a rival to that of Solomon and erected by some ancient Michelangelo might take an honorable place beside our most beautiful buildings,” he wrote. “It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome, and presents a sad contrast to the state of barbarism in which the nation is now plunged.”

It seemed inconceivable to Mouhout that the “barbaric” Khmers could have built Angkor Wat, let alone the other temples and palaces spread around it across some 500 acres (2 sq km). But, the Khmers did build Angkor Wat at the zenith of their once dynamic empire that, founded in 802, fell in 1431 when the rival Ayutthaya (Thai) kingdom to the north sacked Angkor. The seat of the remnant Khmer kingdom moved to Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital today.

Stranded in the jungle

Although Angkor Wat and its attendant cities, temples, reservoirs, terraces, pools and palaces have been a magnetic 21st Century tourist attraction – when I came here in the mid-1990s I would have been one of around 7,500 annual visitors; last year there were 2.5 million, very many from China.

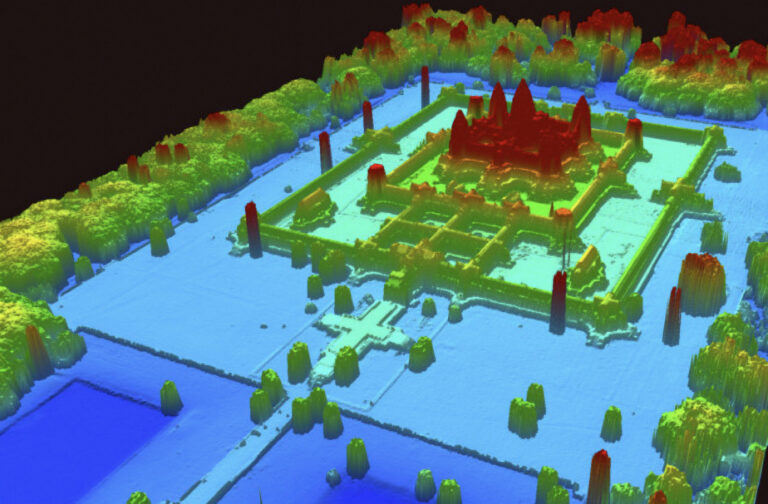

We now know, thanks to the forensic aerial mapping conducted since 2007 by Damian Evans and Jean-Baptiste Chevance, using ground-sensing radar developed by Nasa in the 1960s, that Angkor Wat was the epicentre of a sprawling city at least as big as Berlin. At its zenith during the reign of Jayavarman VII (1181-1218), it was the mighty heart of the largest empire of its time.

Angkor Wat has a massive moat surrounding the central temple complex – seen from the air, the entire site is remarkable for its precise 90-degree angles (Credit: Alamy)

In 2012, Evans, a faculty member of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Sydney and founding member and deputy director of the Greater Angkor Project, and Chevance, an archaeologist with the École française d’Extrême-Orient, founded in 1900, discovered the ‘lost city’ of Mahendraparvata on the plateau of Phnom Kulen. Twenty-five miles north of Angkor, this planned city with its grid of boulevards had been hidden by vegetation for centuries. Founded by the warrior-priest monarch Jayavarman II in 802, it was the ‘template’ of Angkor and its great temple. Since 2012, Mahendraparvata has proved to be even bigger than Evans and Chevance had first thought.

This drawing of the temple’s façade was made by Henri Mouhout, a French explorer who visited the site in the mid 19th Century and could not believe his eyes (Credit: Wikipedia)

The discovery of this city was only possible thanks to Lidar, a form of aerial laser scanning that, mounted in helicopters, sees through the ground below, identifying streets and buildings where all the human eye can see is fields and forests. Expensive until recently, the technology is now available to archaeologists and, operated in the near future by drones rather than helicopters, it may well enable them to make further astounding discoveries, especially of fabled ‘lost cities’.

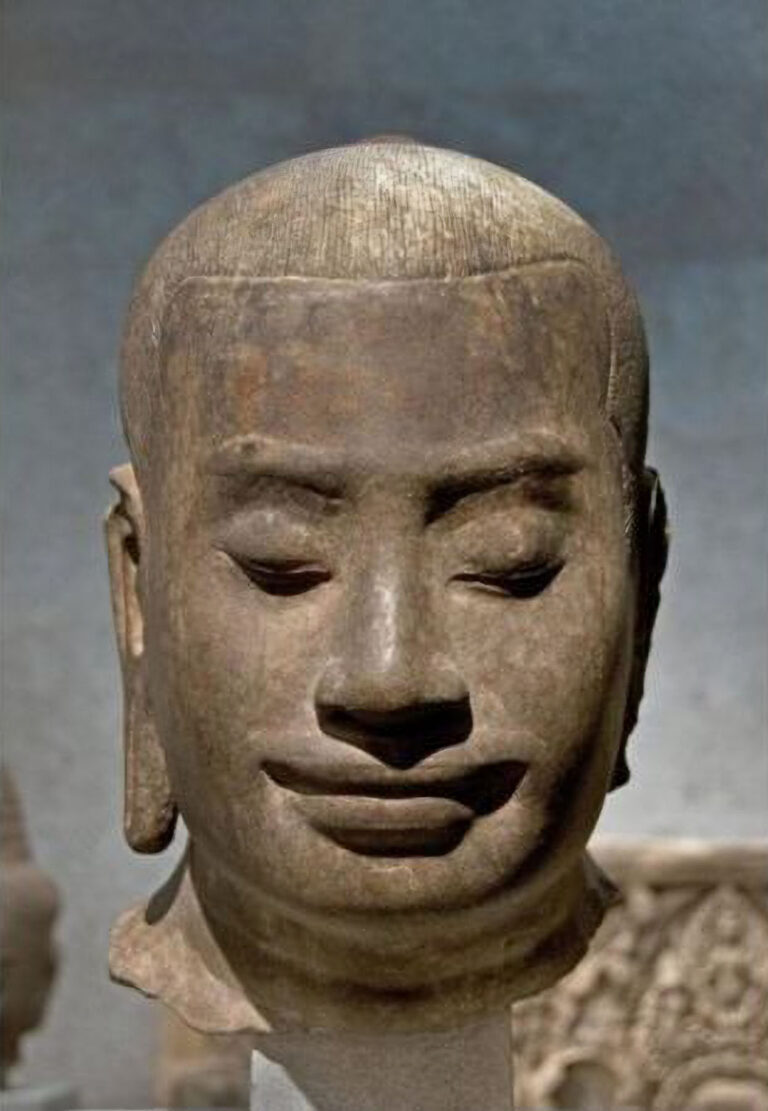

Jayavarman VII was the ruler of the Khmer Empire from 1181 to 1218 and is widely regarded as its most powerful leader – he oversaw the completion of the temple (Credit: Alamy)

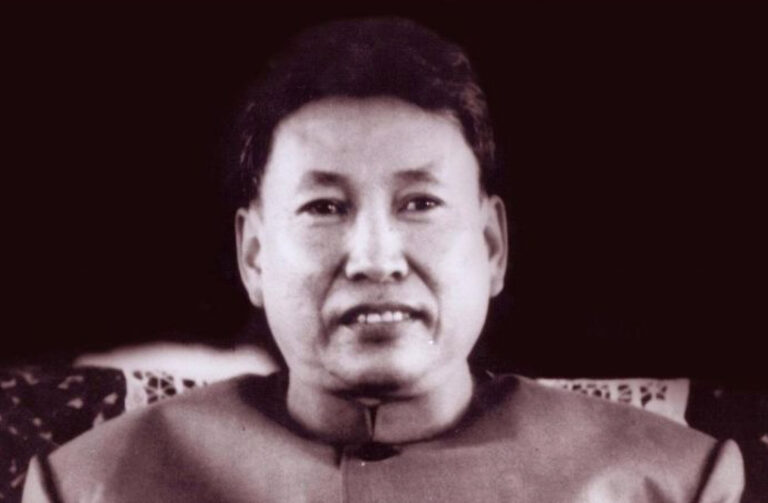

It may have been possible to make such discoveries some years earlier in Cambodia, but until 1998 Phnom Kulen was the last refuge of Pol Pot and his murderous Khmer Rouge, the fanatical Communist organization that ruled the country from 1975 to 1979, executing and starving to death some two million people, or a fifth of the population. The area remains alive with landmines.

If the discovery of the scale and ambition of Mahendraparvata was a remarkable event, the uncovering of the sheer scale of Angkor has been mind-bending. From its moated temple with its lotus-bud towers, its courtyards and galleries, friezes of warriors, kings, demons, battles and three thousand heavenly nymphs, all shaped in thirty-seven years by 300,000 workers and 6,000 elephants, or so inscriptions say, from millions of sandstone slabs floated down from Phnom Kulen, Angkor stretched for miles around.

Urban planning

This, perhaps, was the first low-density city – a phenomenon normally associated with the railway age, the car and the spread of suburbia – a vast-reaching conurbation, its parts linked by an ambitious network of roads and canals, reservoirs and dams carved from the forest.

What’s more, Khmer cities were connected to one another, so the “built-up” area of Angkor seems to have been bigger than anyone today, much less barefoot 16th Century Portuguese friars, has been able to figure. An enormous and intricate irrigation system mapped by Evans and Chevance provided Angkor with food – rice for the main part – and yet the ever-increasing scale of this engineered and well populated landscape was, it seems, its undoing.

The Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot, were responsible for the deaths of almost a quarter of Cambodia’s population – they held out near Angkor Wat until 1999 (Credit: Alamy)

Put simply, Angkor overreached itself – like many modern cities worldwide today. It was not simply military invasion from what is now Thailand that hastened the fall of the Khmer Empire, but the imperious ambition of rulers and cities. What proved to be overpopulation caused unsustainable deforestation, the degradation of topsoil and the overworking of the irrigation system that would have required a huge workforce to keep it in a permanent state of good repair.

For all the raised roadways with rest houses sited every 15km (9 miles) and hospitals built by Jayavarman VII, who used ambitious architecture and grand plans to keep the peace as well as to express the confidence and culture of the Khmer Empire, the jungle would reclaim these mighty works.

Angkor today, along with such romantic temples as Jayavarman VII’s Ta Prohm, where enormous cotton silk trees and their fairy-tale roots appear to hold the architecture in wild embrace, and known to cinema goers through the film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), is threatened anew not by invading armies but by mass tourism. Already, brash new ‘luxury’ air-conditioned tour-group hotels, featuring swimming pools, hot tubs and spas, dominate the once small French Colonial town of Siem Reap, no longer a walk, but now an air-conditioned coach ride from Angkor Wat.

Such is the use of water by the millions of tourists heading this way each year that the water table of the area under sandy soil is threatened. Its decline is damaging the very stones of the 12th-Century temple; meanwhile, visitors take photographs of themselves and shout into their mobile phones.

As laser-mapping technology becomes more readily available, perhaps archaeologists might help to divert some of the millions heading to Angkor Wat to elsewhere in Cambodia and Southeast Asia. Even so, what Angkor has that will keep drawing the crowds is the world’s biggest temple – and one that remains enigmatically magnificent.